Responsible Software Engineering

This book is written based on the author’s observations of colleagues at Google.

Disclaimer: This is a personal summary and reflection, not a substitute for the original book.

What Is Responsible Software Engineering?

Definition

Responsible software engineering means developing software products that benefit society while avoiding harm to the planet and its inhabitants.

What does that mean? It includes:

- Social benefit — serving the public.

- Not harming the planet — reducing carbon emissions.

- Not harming inhabitants — avoiding physical, economic, psychological, or other harms to people (and “inhabitants” includes non-human life when relevant).

Responsible engineering isn’t only about the technology itself—it’s about understanding the social context in which the technology is deployed.

For example, suppose you build the world’s most powerful mapping application that finds the most efficient route. Responsible design means not only calculating optimal paths—it also means considering the social impact on communities along those paths.

Once people start using your app, traffic might flood neighborhoods that were previously quiet—causing congestion, accidents, and pollution.

This means you may need to collaborate with these communities to mitigate negative side effects.

The Five Ethical Principles of AI

Be Socially Beneficial

Technology should serve public welfare—not just ads or profits. Speaker O shared how they used the UN SDGs as a filter to find real problems to solve, from fire detection in Street View to AI for recycling.Avoid Unfair Bias

To prevent discrimination from being encoded into AI, adversarial testing is essential.

Examples:

Google Translate adding gender-inclusive pronouns;

improved datasets for dark-skinned users to reduce face-recognition errors.Be Built and Tested for Safety

Safety must be designed in, not patched later.

Borrowing from aviation and nuclear systems, developers must set boundaries early—before deployment.Be Built and Trusted for Interpretability

AI should explain why it made a decision.

From “Why am I seeing this?” UI elements to basic AI literacy in K–12 education, interpretability builds trust.Privacy Must Be Equally Available

Privacy should not be a luxury feature.

Speaker P cited the 2019 NYT editorial: “Privacy must be universal.”

Technologies like federated learning aim to ensure both fairness and safety.

Building AI Systems That Benefit Everyone

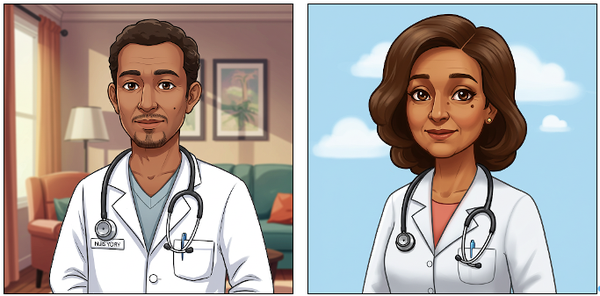

Figure 2-1 shows AI-generated images reinforcing stereotypes:

- Doctors as men

- Nurses as women

- Laborers as people of color

What Is Fairness?

Fairness issues directly impact people’s lives. Examples:

- In 2016, Joy Buolamwini at MIT found that face-recognition systems couldn’t detect her face due to insufficient training data from people who look like her.

- A well-known AI image generator disproportionately rendered CEOs as white men and drug dealers as men of color.

- A fire-risk prediction model underestimated risks in low-income communities whose data was less reliable.

Why Is Fairness Hard?

- Fairness ≠ accuracy.

- Fairness is contextual and relative.

- Bias always exists.

- Ambiguity in AI inputs is unavoidable.

- AI outputs can be difficult to evaluate.

Ambiguity in AI Inputs: When One Command Can Cause Disaster

I once read about an open-source project integrating an AI chatbot into the Linux command line.

Users could type natural language commands, and AI would generate shell commands.

I tried the prompt:

“Make all files in the current directory read-only.”

The AI returned:

1 | chmod -R 444 * |

If you’re a Linux engineer, that command should terrify you.

Here’s why:

1. -R Recursively modifies all subdirectories—never requested.

AI over-extended the meaning of “all,” assuming I meant every file recursively.

2. 444 grants read access to everyone.

This exposes data that should remain private.

3. Hidden files are ignored (* skips dotfiles).

AI didn’t ask for clarification.

And the worst part:

Permission changes are extremely hard to revert, often breaking systems or blocking critical operations.

A responsible design would have asked:

- “Do you want to include subdirectories?”

- “Who should retain read access?”

- “Should hidden files be included?”

Reducing the Carbon Footprint of Code: The Invisible Responsibility

Software is invisible, but its energy consumption is very real.

Every program we run produces carbon emissions.

On a laptop, emissions are small.

On hundreds of thousands of CPUs in a data center using fossil energy? Massive.

Even apps on your phone accumulate emissions through daily charging.

Three Core Strategies for Carbon-Aware Software

1. Processor Usage

How many CPUs?

For how long?

Can loops or polling be reduced?

2. Location

Running workloads in data centers powered by renewables drastically reduces emissions.

3. Time of Day

Some power grids use more renewable energy at certain hours.

Google has even published “carbon-intensity schedules” for batch workloads.

Practical Optimization Approaches

- Reduce CPU cycles → optimization = decarbonization

- Reduce memory → less garbage collection

- Reduce network traffic → fewer transfers, less energy

- Capacity management → avoid idle resources

High-quality cloud providers offer metrics such as:

- CPU idle rate

- Unused memory

- Unallocated disk space

These help engineers right-size resources.

Building a Culture of Responsible Software Engineering

Principles alone accomplish nothing.

To make responsibility real, organizations must solve six challenges:

- Policy Creation — What values does the company prioritize?

- Communication — How do we educate engineers consistently?

- Process Design — How do we embed responsibility throughout development?

- Incentives — People choose the path of least resistance; we must reward good behavior.

- Learning from Mistakes — Systematic documentation prevents repeated failures.

- Measuring Success — Ethics must be made measurable.

Case Study: Google’s Responsible AI Principles

In 2018, Google released principles including:

- Social benefit

- Avoiding bias

- Safety

- Accountability

- Privacy

- Scientific excellence

- Use restrictions ensuring alignment with principles

But when EngEDU interviewed engineers:

No one could recite even one principle.

Principles existed—but weren’t internalized.

This reflects a universal challenge:

Principles aren’t hard to write.

The hard part is making people remember, understand, and apply them.

Discussion: Responsibility × Innovation

How should organizations challenge technological ethics?

By teaching engineers reflection so they can identify risks—not just follow instructions.

Is open source more ethical?

Open source enables broad scrutiny and diverse input, reducing some risks.

But openness ≠ ethics.

It simply creates more opportunities for improvement.

Conclusion: Technology Is Only as Good as the Values Behind It

From dangerous shell commands to biased models, energy consumption, and cultural gaps within teams—we’re facing one fundamental question:

Technology is neither good nor evil by nature.

It amplifies the values we embed into it.

Responsible software engineering is not bureaucracy.

It is a mindset that asks:

- Could this code be misused?

- Is this model fair?

- Could this system cause harm?

- Are resources used responsibly?

- Do we truly understand what we’re building?

The stronger technology becomes, the greater its externalities.

Responsible engineering ensures we don’t make the world worse by accident.

As AI, software, and global systems evolve—

the future will be shaped not by machines, but by the choices of engineers, designers, and researchers.

We only need to ask:

When this technology reaches the world,

who do we want it to benefit, and how?

If the answer brings more kindness, less bias, and less harm—

then we are indeed building a future worth believing in.